Making Sense of Money Laundering

Insights for Creditors and Claimants

Searching for Assets and Income

People who conspicuously flaunt their wealth tend to draw attention. For criminals, this means heightened scrutiny from law enforcement and tax authorities – putting their assets at serious risk. Civil forfeiture laws entitle state and federal governments to seize real estate, vehicles and other property used to facilitate a crime, even if the owner has not been formally charged with a criminal offense. Criminal assets are further susceptible to surrender through post-conviction restitution orders, tax levies and civil judgments. In response, certain offenders – particularly those engaged in white collar and organized crime – have learned to pose as law-abiding citizens with clean hands, someone whose high-net-worth financial profile will not arouse suspicion.

Money laundering is the process by which criminals attempt to disguise their illicit income, making it appear to have been earned by legitimate means, so they can freely spend and enjoy their wealth. More advanced methods of money laundering can withstand scrutiny by tax authorities and financial regulators.

Money laundering is also used to ‘muddy the waters’ after financial crimes have been committed, aiding perpetrators in their efforts to disappear with the proceeds. Methods known as layering, smurfing and mules are used to mix, conceal and control the flow of money. They are intended to protect perpetrators from being identified through forensic financial analysis – and to prevent stolen, tainted or misappropriated funds from being tracked to their ultimate destination.

Laundering activity may be detected during asset searches to support financial recovery from corporate fraud, Ponzi schemes and white collar crimes. Similar schemes to conceal income and assets can also be uncovered – sometimes unexpectedly – by creditors, claimants and legal counsel during civil matters that seem otherwise routine, such as judgment enforcement, transactional due diligence or divorce proceedings. Learning to recognize evidence of laundering – understanding why, where, and how it is done – can be critical for bringing these cases to their clearest possible conclusion.

Placement, Structuring & Smurfing: Dirty Cash into Clean Deposits

Multiple channels are used to introduce ‘dirty money’ into the mainstream financial system. They commonly include businesses that handle large amounts of cash, such as casinos, bars and restaurants. These businesses can be used to fabricate records of conventional revenue, by filling the general ledger with fictitious receipts of sales to non-existent customers. The establishments do not need to be popular, or profitable, for these schemes to succeed. Every tainted dollar is rinsed clean as it moves from the business books, to the bank, then back to the owners’ pockets.

Financial institutions in the U.S. and Canada are required to inform the government of cash transactions totaling more than ten thousand dollars. Currency reporting and recordkeeping requirements are a part of anti-money-laundering (AML) regulations in many countries, forcing criminals to adapt their practices accordingly.

One step taken to avoid scrutiny at the bank is to split large amounts of cash into a series of smaller deposits. Organizing transactions to stay under reporting limits is known as structuring. This method is not foolproof. Financial institutions with robust AML compliance programs use automated systems to detect suspicious patterns, such as a series of deposits just below the reportable threshold, which could trigger a report to regulators. Structing is a criminal offense with serious consequences, which can lead to a full-blown investigation and asset search for the true source of suspect funds.

Financial institutions and money services businesses are required to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) for any suspected incidents of fraud, money laundering or other violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). The number of SARs filed annually has increased more than 50 percent over the past two years, and is expected to exceed more than 2.0 million in 2023, according to recent reporting by The New York Times.

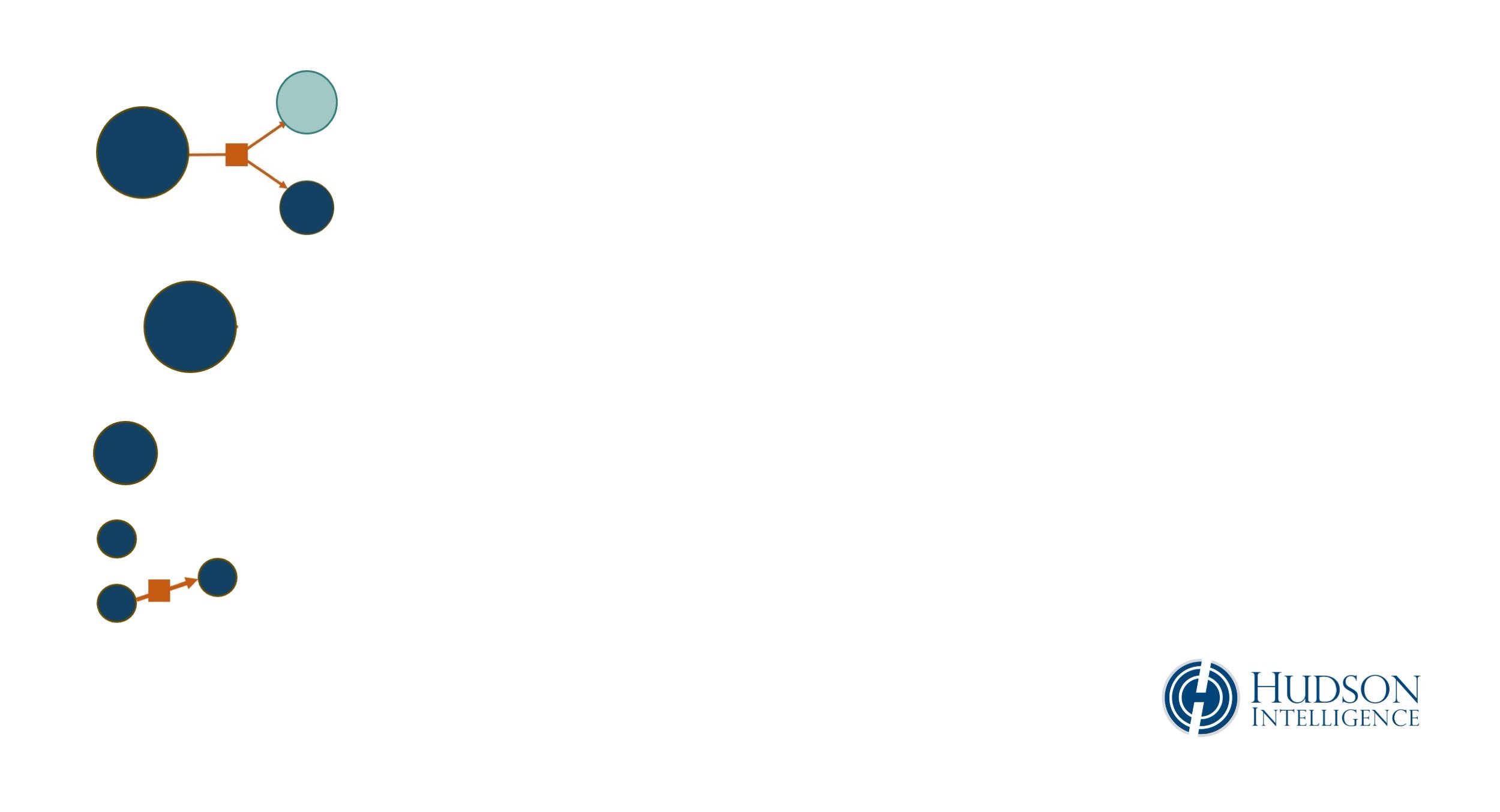

A more advanced version of structuring requires a team of accomplices to spread funds across accounts under separate identities at different banks. This method is referred to as ‘smurfing.’ The phrase comes from the narcotics trade, where so-called smurfs are used to purchase items containing precursor chemicals needed to cook methamphetamine. By themselves, most of these ingredients may be unremarkable – iodized salt, coffee filters, brake fluid, drain cleaner, etc. – but meth shoppers who try to purchase everything at once may be reported to local police. Sending associates to obtain each item individually, in smaller amounts from multiple stores, reduces that threat dramatically. In a similar fashion, distributing cash across a group of seemingly unrelated people – rather than relying on a single depositor – reduces the risk that suspicious transactional patterns will be detected by banks or regulators.

Layering: Muddying the Stream of Dirty Money

Layering is a technique for obscuring the origin and destination of illicit funds by moving funds through a lengthy chain of extraneous transactions, making the trail of money more difficult to track by forensic analysts and law enforcement.

Layering is frequently encountered during investigations of cryptocurrency-based crimes, including investment scams, hacks and thefts. Digital assets on a blockchain are identified by their address, a long string of letters and numbers – such as 1A1zP1eP5QGefi2DMPTfTL5SLmv7DivfNa – that serves as a virtual location for storing, sending and receiving assets. An address is similar to a bank account number. However, unlike accounts at a bank, cryptocurrency users can create and control their own addresses without any institutional oversight.

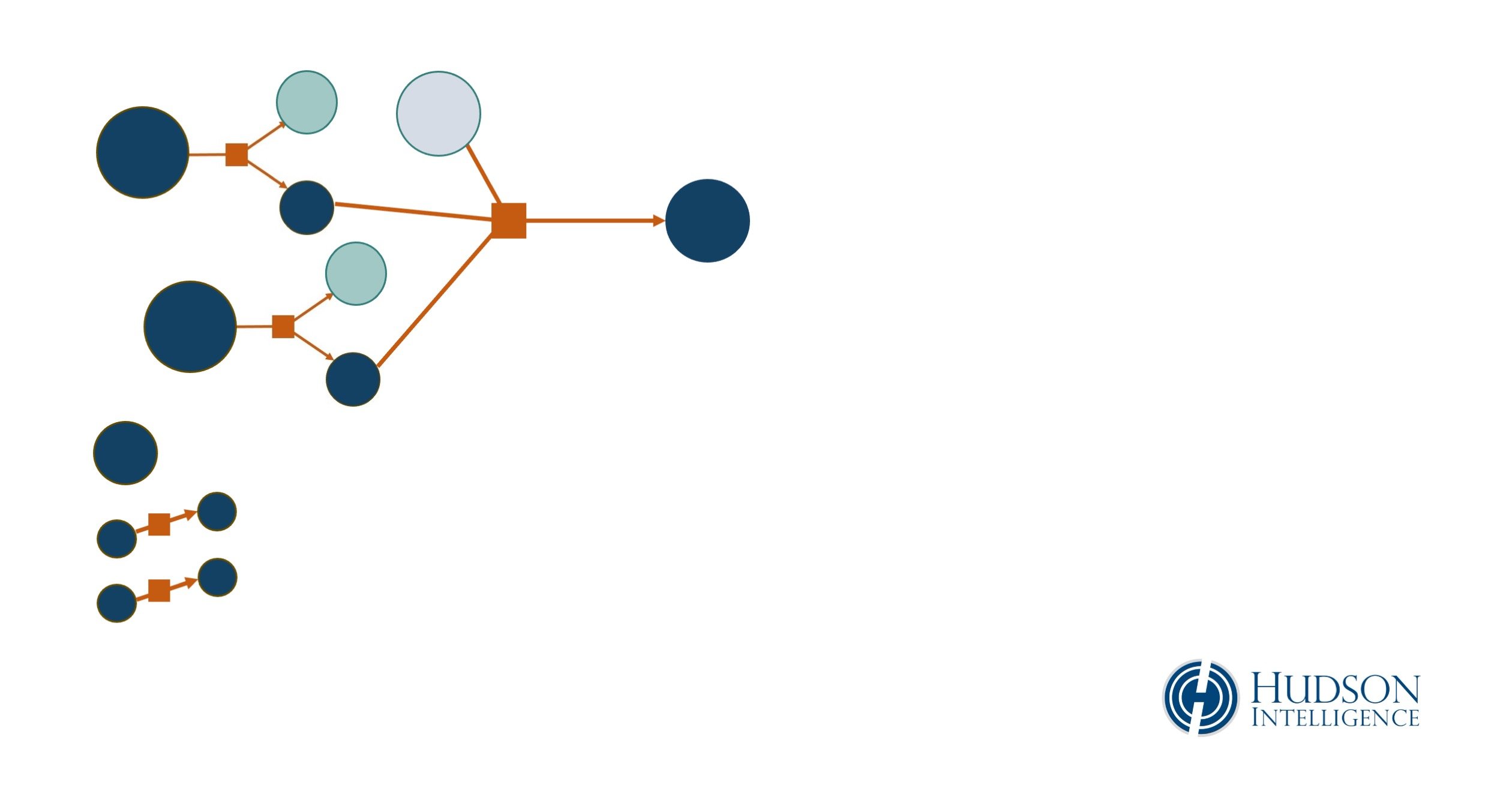

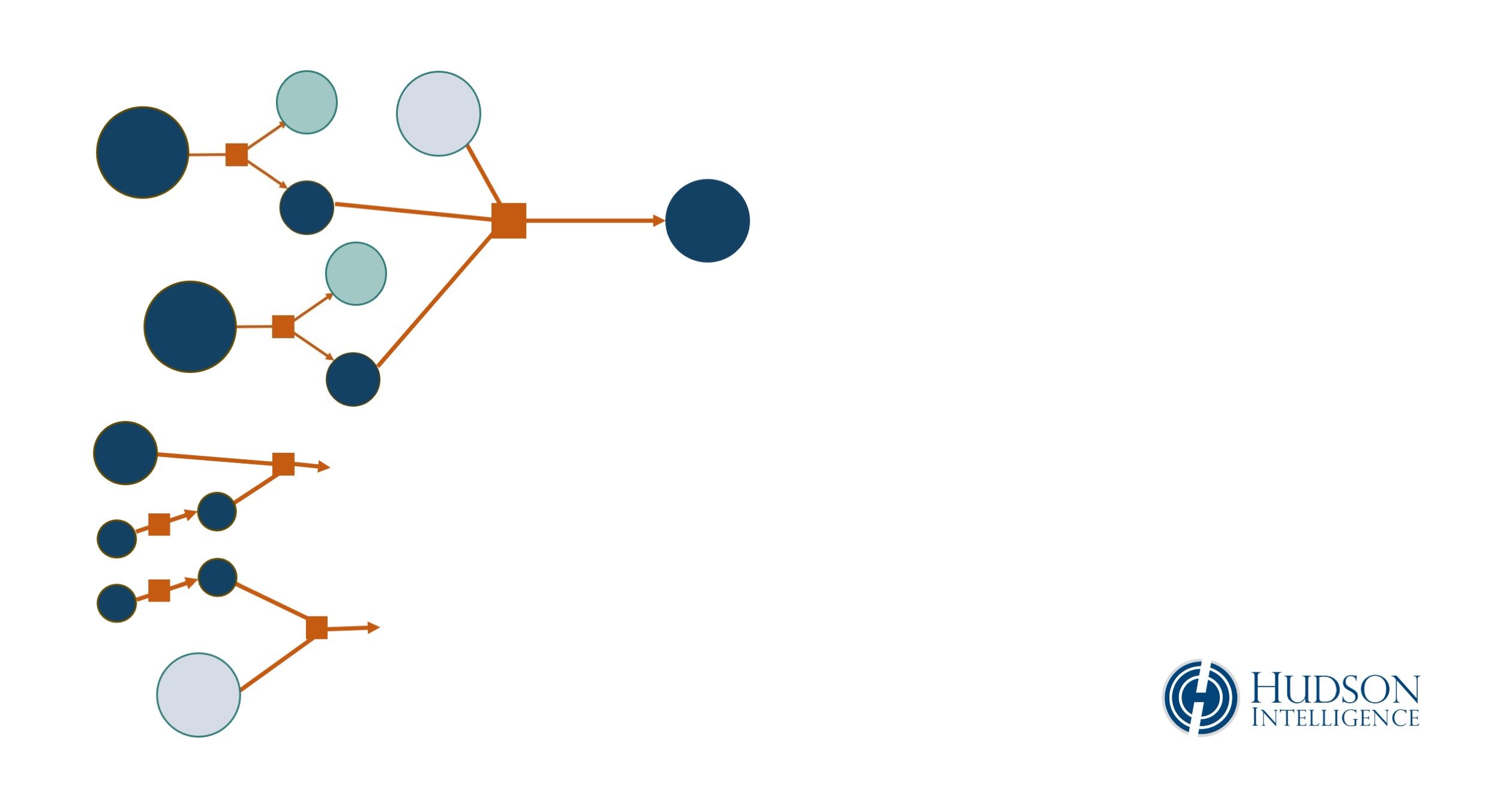

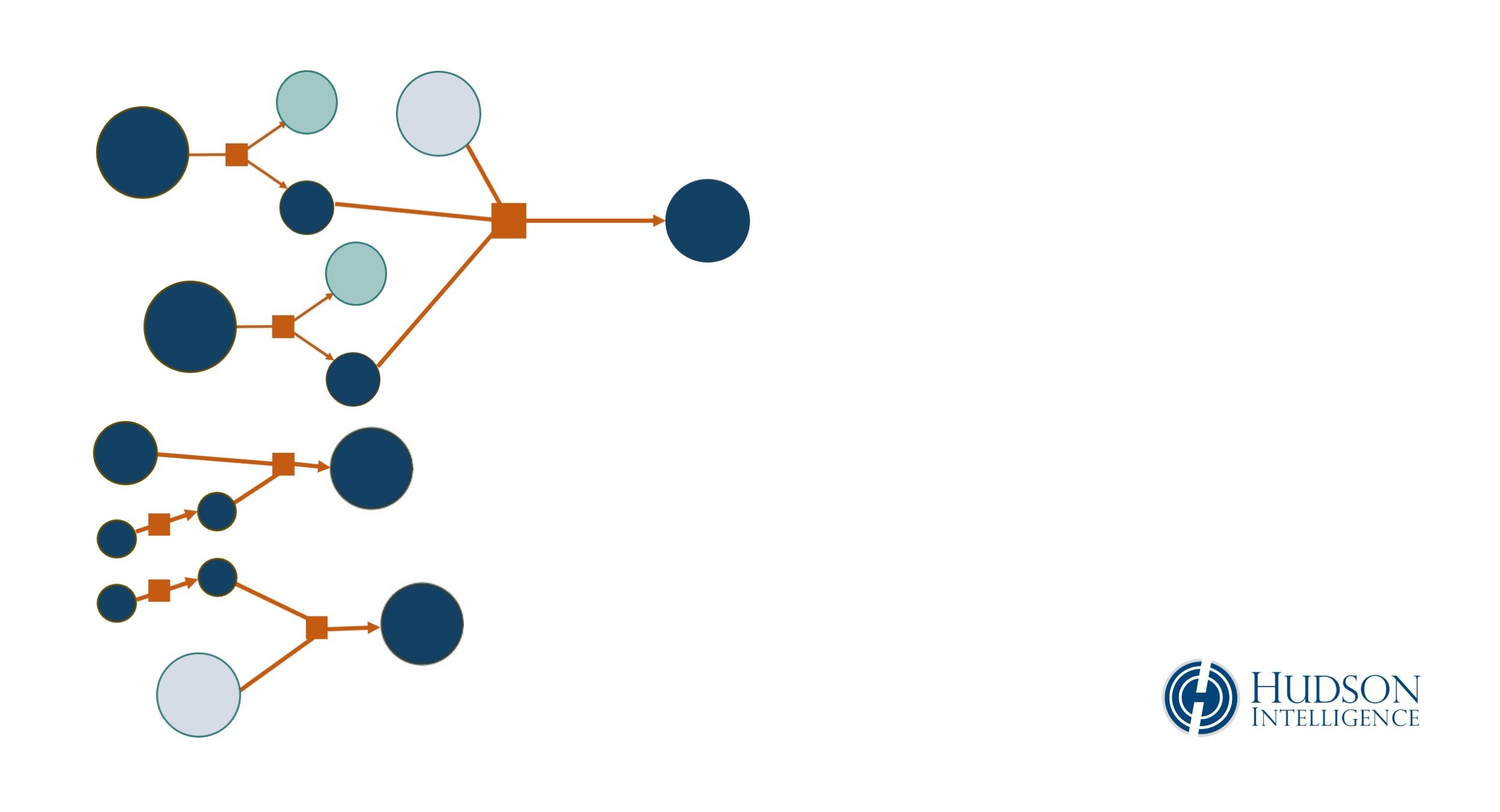

Fraudsters and thieves transfer illicit assets through large pools of addresses under their direct control. Script-based trades can automatically split, move and reconsolidate the same assets through hundreds or thousands of “hops” before being deposited to their ultimate destination. Cryptocurrency can be further layered through coin mixers, decentralized finance (DeFi) and peer-to-peer exchanges. Many of these third-party trading platforms do not attempt to verify the customer’s identity or source of funds, making them ideal environments for money laundering.

By moving funds through these kinds of complex mathematical mazes, it becomes more difficult and time-consuming for an outside observer to manually trace the flow of tainted assets on a blockchain. In response, cryptocurrency intelligence firms have developed sophisticated toolsets with algorithm- and heuristic-based analytics that automate portions of the asset-tracking process, such as identifying ‘clusters’ of closely associated addresses. Advanced tools and technical expertise are essential elements for successful asset searches of crypto crimes.

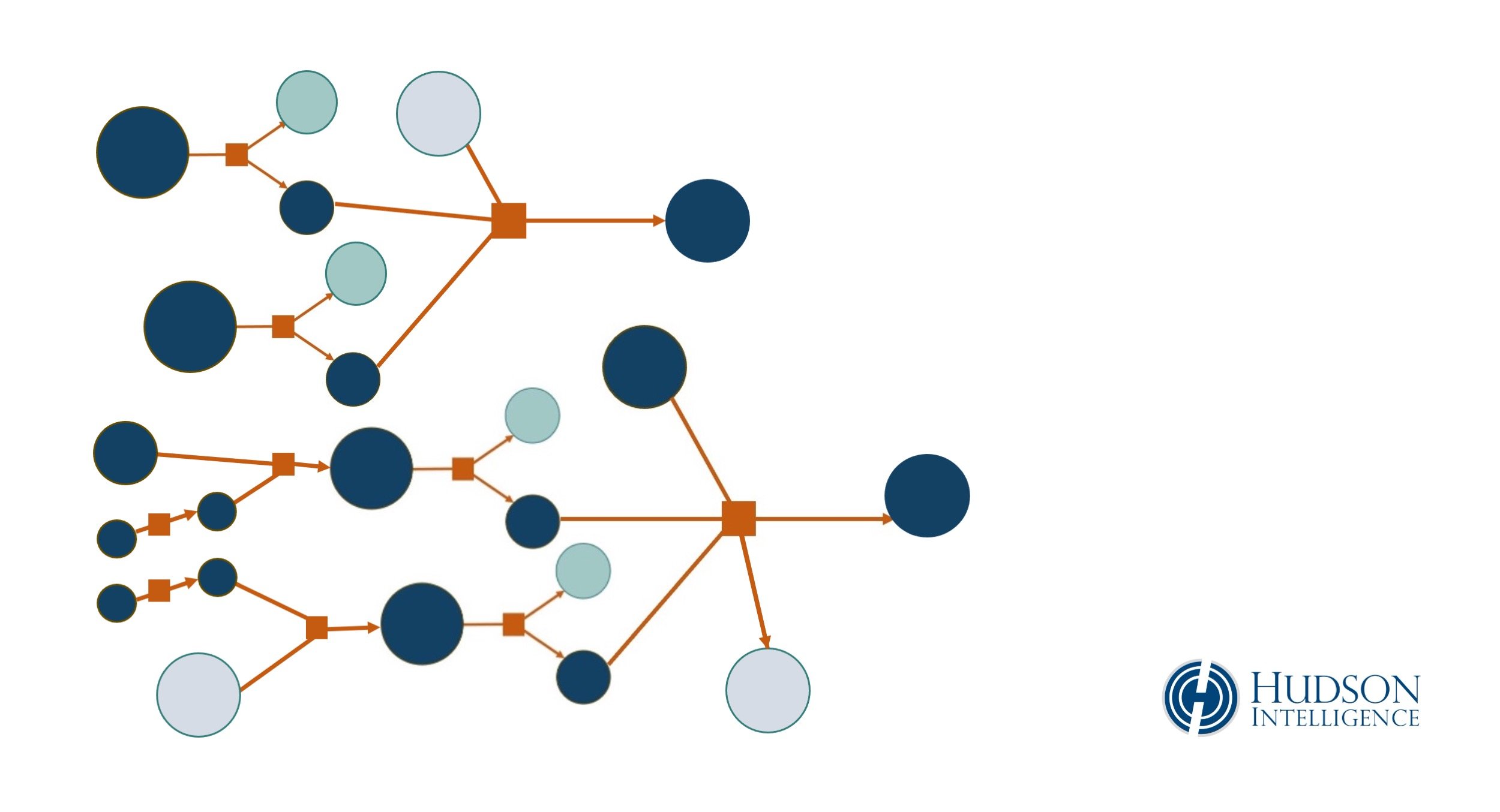

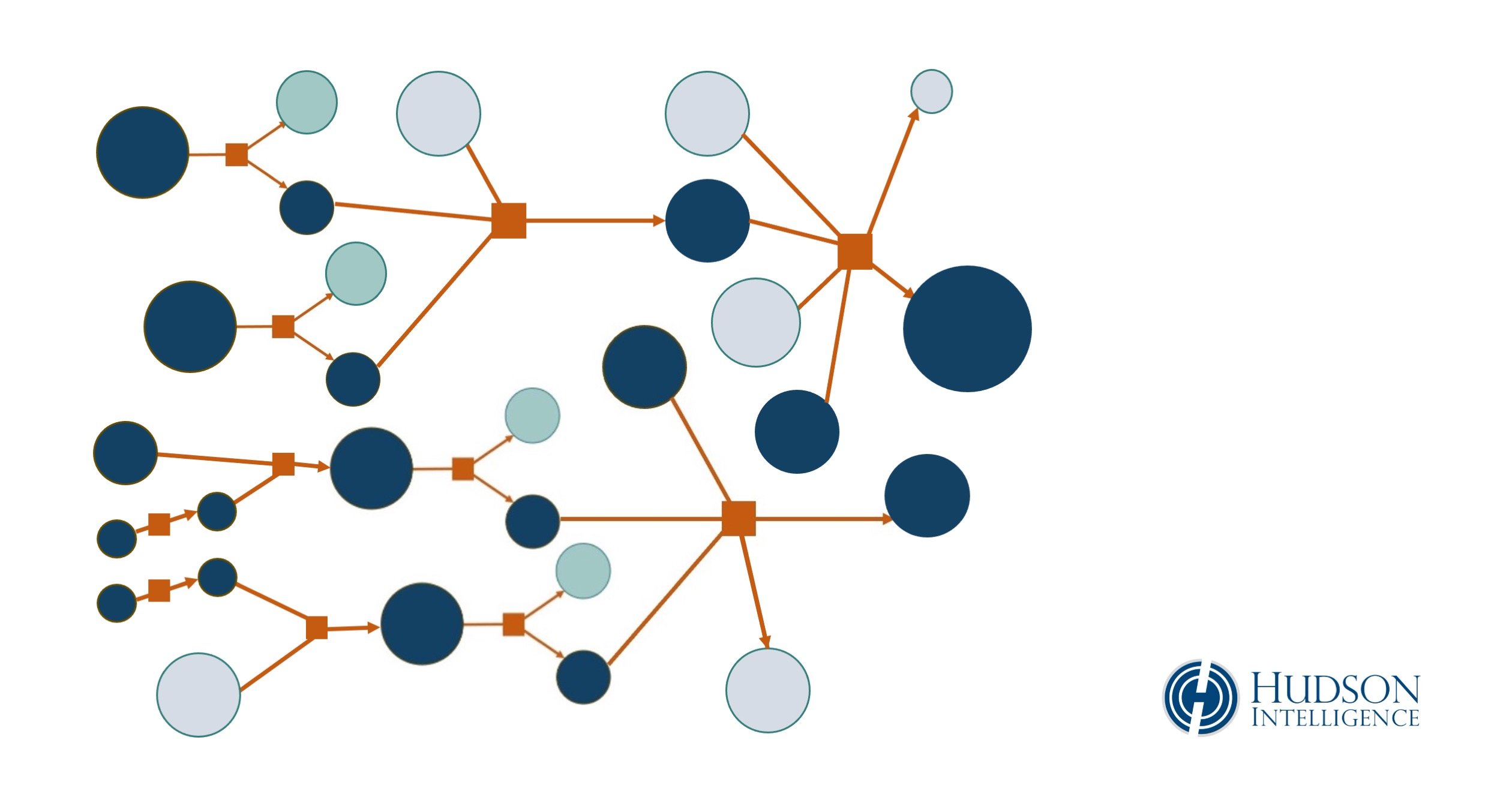

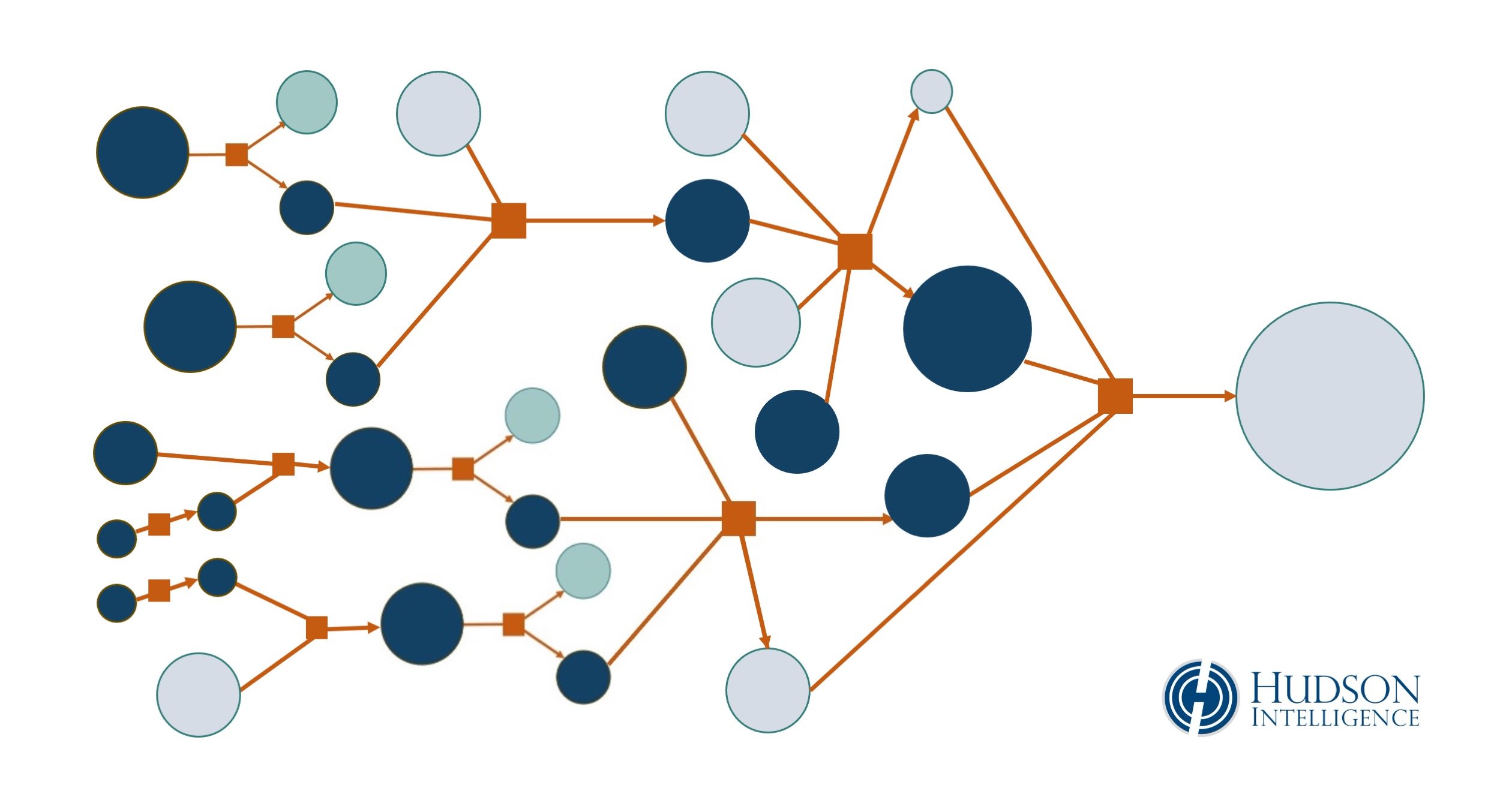

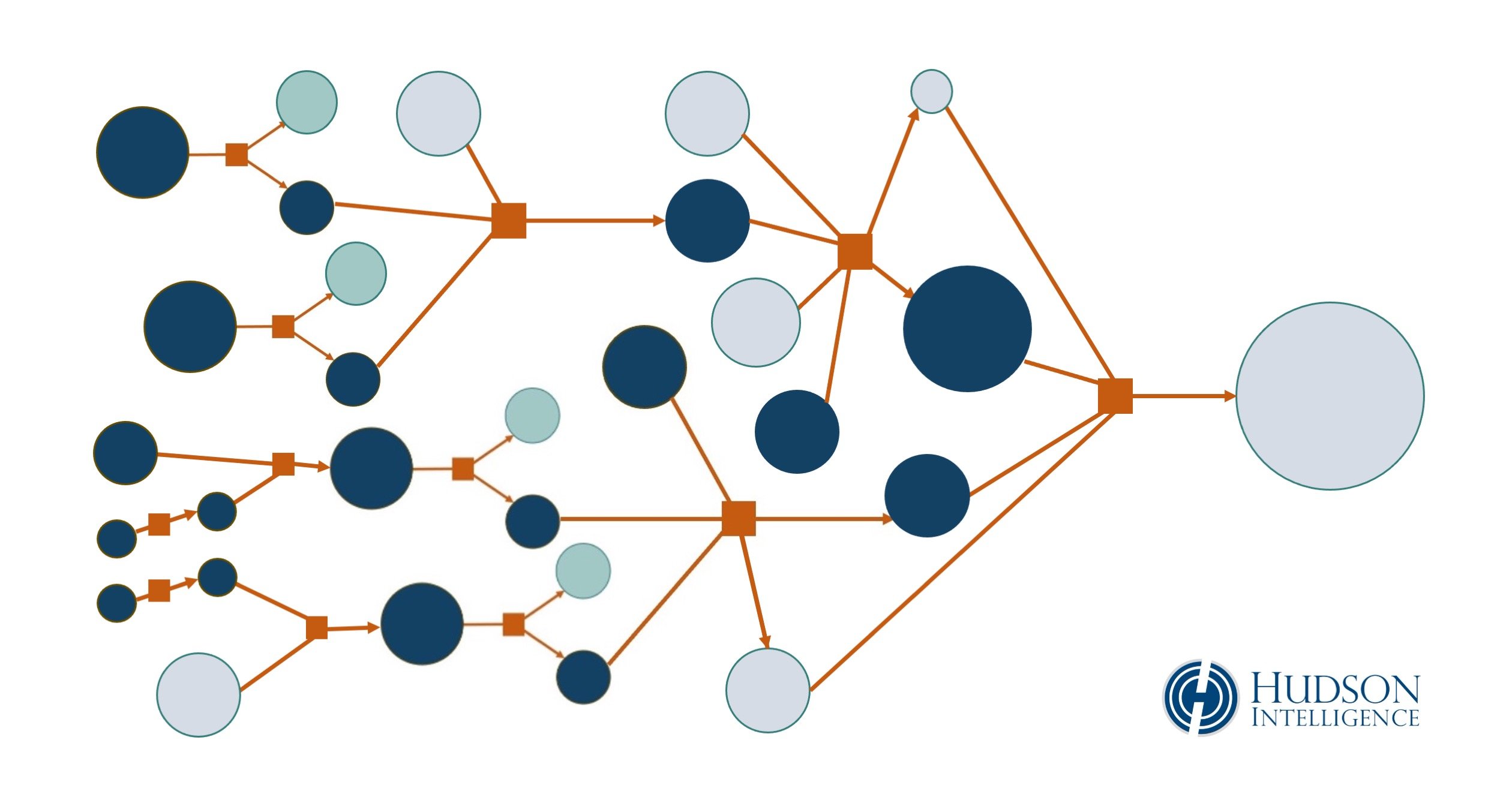

Illustrated below is a visual depiction of layered transactions, similar to how such data is rendered by blockchain intelligence tools. It shows a complicated jumble of transactions culminating in a final large-value transfer. The output address in this example reflects a consolidation of scattered assets controlled by the subject of an investigation.

Financial Sectors Susceptible to Money Laundering

An estimated $300 billion is laundered through the U.S. annually. Anyone looking to launder millions of dollars – or hundreds of millions – must find more sophisticated means to wash money at scale. Non-transparent and lightly regulated markets are ideal for these purposes. The extent of laundering activity is a serious concern in opaque sectors such as private equity, hedge funds, fine art and antiquities. Laundering may also be concealed in plain sight, behind a pretense of public benefit: vanity charities and fake non-profits have been abused by dubious donors looking for a respectable-seeming place to park their money.

Real estate deals, in particular, can be attractive for launderers who want to wash large sums in a single transaction. A degree of privacy is accepted when buying and selling high-end properties, which are frequently acquired through special-purpose entities or trusts with undisclosed ownership. Piercing the veil of secrecy for opaque entities controlled by a debtor can be a critical factor during asset searches for recovery from financial crimes and enforcement of civil judgments.

Money laundering in real estate may also involve employing “strawmen” who buy and sell on behalf of undisclosed owners. Flipping houses between co-conspirators can quickly generate a paper trail of fake profits. Prices can be further manipulated with collusion from developers or other industry insiders such as brokers and appraisers.

Long-exploited loopholes for anonymous cash purchases of luxury property may soon be closing. Regulatory concerns have led to a forthcoming rule proposal from FinCEN, which would require title companies to disclose the identities of individuals using shell companies or trusts to acquire real estate, according to Thomson Reuters.

Going Global in Offshore Havens

Higher levels of money laundering often involve moving funds through accounts in other countries and offshore havens. Transferring assets through a global tangle of transactions creates roadblocks for law enforcement, forcing them to seek assistance from foreign counterparts in places where cooperation and transparency are not equally assured. Financial institutions may also refuse to comply with court orders, subpoenas and warrants that originate outside their local jurisdiction.

Online banking and electronic funds transfer (EFT) have made it progressively easier and more affordable for launderers to move their money offshore. Low-cost service providers in pass-through economies such as Luxembourg and the British Virgin Islands offer cheap formation of shell companies, mail forwarding, and related services that can be used to create a paper empire of special-purpose entities with accounts at local depositories. Nominee services also ‘rent’ the name of local citizens to be listed in corporate filings as directors of shell companies, concealing the identity of their ultimate beneficial owners. Detecting connections between service providers and nominee officers used by a debtor can be an important consideration when searching for assets abroad.

Tax Evasion: Flip Side of the Same Coin?

It is not uncommon to conflate money laundering with tax evasion. Though there are similarities between these financial crimes, they tend to have different methods and objectives.

Tax evaders typically make false or fraudulent claims to misrepresent their financial situation in order to pay less in taxes than they owe. Common tactics of tax evasion – such as underreporting earnings or inflating deductions – are intended to make net income decrease on paper. This is arguably the opposite goal of launderers aiming to make reportable, lawful-looking income increase by fabricating records of phony revenue streams.

Consider Al Capone. As head of the largest organized crime syndicate in Chicago during Prohibition, Capone amassed a personal fortune estimated at around $100 million in the 1920s, equivalent today to $1.5 billion. Despite enjoying a luxe high-profile lifestyle, he never filed a federal tax return, insisting he had no taxable income. His tax evasion was total. If he had instead laundered the millions of dollars flowing to him from moonshine, gambling and other mob rackets – creating a paper trail of ‘clean’ income, and paying some nominal sum of tax liabilities – he might have been better prepared to defend himself against criminal prosecution for tax evasion. Instead, he ended up at Alcatraz.

Consult an Investigator

Hudson Intelligence assists law firms, businesses, public agencies and investors with investigative due diligence, international asset searches and investigations of complex frauds and financial crimes. Investigations are conducted by our staff of Certified Fraud Examiners and Cryptocurrency Tracing Certified Examiners. If you would like to discuss a potential investigation, please complete the form below.